This one is mine

A story about the economics, duties, and privileges that come with being a citizen of startups.

Most people don't talk about the economics of the startup journey; it's gauche to talk about money. But... since when is it tacky to help others think through a life-changing financial and career decisions?

Here’s my story of 11 years in startups — first as an early employee, then as a founder. Mostly focused on personal finance (equity, salary) with a sprinkling of the non-monetary stuff.

Betting big

I joined a startup in 2015 as the first employee. This meant a pretty big haircut on base salary, from the ~$180K / year that I’d just made as a management consultant in Chicago, to $100K / year in San Francisco.

$100K doesn’t go far in San Francisco; I had 2 roommates and didn't live in an expensive area, and I was still barely breaking even.

My original offer was 0.5% equity. I negotiated that up ~2x, to ~1%. The founders said the company was currently raising at $25-30M, so this translated to ~$300K of equity over 4 years (approximately compensating for my paycut).

In the years that followed, I loaded up on equity. In fact, I asked for a 50% paycut in 2016, to get the difference in more shares. Hilariously: I did this when the company was in the middle of an SEC subpeona, and our revenue had gone to ~$0 because we had suspended trading operations. That's how bullish I was. A little while later, I also scrounged up my ~$50K in life savings to buy secondary shares from one of my colleagues who was in a cash crunch.

After the SEC stuff was sorted out, the company grew rapidly. Between 2016 and 2018, we grew from ~$0 to ~$30M in annualized revenue, with a team of ~20. I didn’t believe in commissions for early employees in a brokerage business. We weren’t building a boiler room, we were building an exchange; so I always pushed back on the idea. This meant that none of the employees benefited from the hundreds of millions of dollars in deals we closed (except for one; unknown to me, one of the team members had negotiated a secret deal with the founders). At any rate, I’m not sure if I’d have let myself benefit from the ~$10M in revenue I was responsible for closing; I was the COO and I really believed — even if we were to do commissions — that executives should eat last.

Many of these choices feel naive in retrospect, but I don't regret a thing.

I left in 2018, after... irreconcilable differences with the founders. I left with a sense of peace, knowing that I couldn’t affect the future of the company anymore, but I gave it my all when I was there.

This is why it rankles me sometimes when people idolize founders... I was “just an employee,” but I embodied founder mode.

Founder mode is a mindset, not a birthright. This experience inspired another piece I wrote, An Ode to Early Employees.

Looking back, I wish I’d understood some of the personal sacrifices better:

Crazy hours: I averaged one all-nighter a week, and slept in the office all the time. 996 would have sounded like a vacation.

Psychosomatic conditions: excruciating back pain, shout out to Dr. Luck in SoMa for fixing it; waking up in a cold sweat so often I started putting a towel under myself when I went to sleep; routine panic attacks by 2018.

Strain on personal relationships: my wife said on our honeymoon that she never wanted to go on a vacation with me again. (Over the years since, I’ve figured out some semblance of balance and sanity.)

How it played out

I think most early employees understand that, in almost all cases, it doesn't work out. Most early stage startups shut down, or get acquired for a nominal amount which doesn't clear the preference stack.

In our case, it "worked out" — the company went public for $2B in 2022. Hooray!

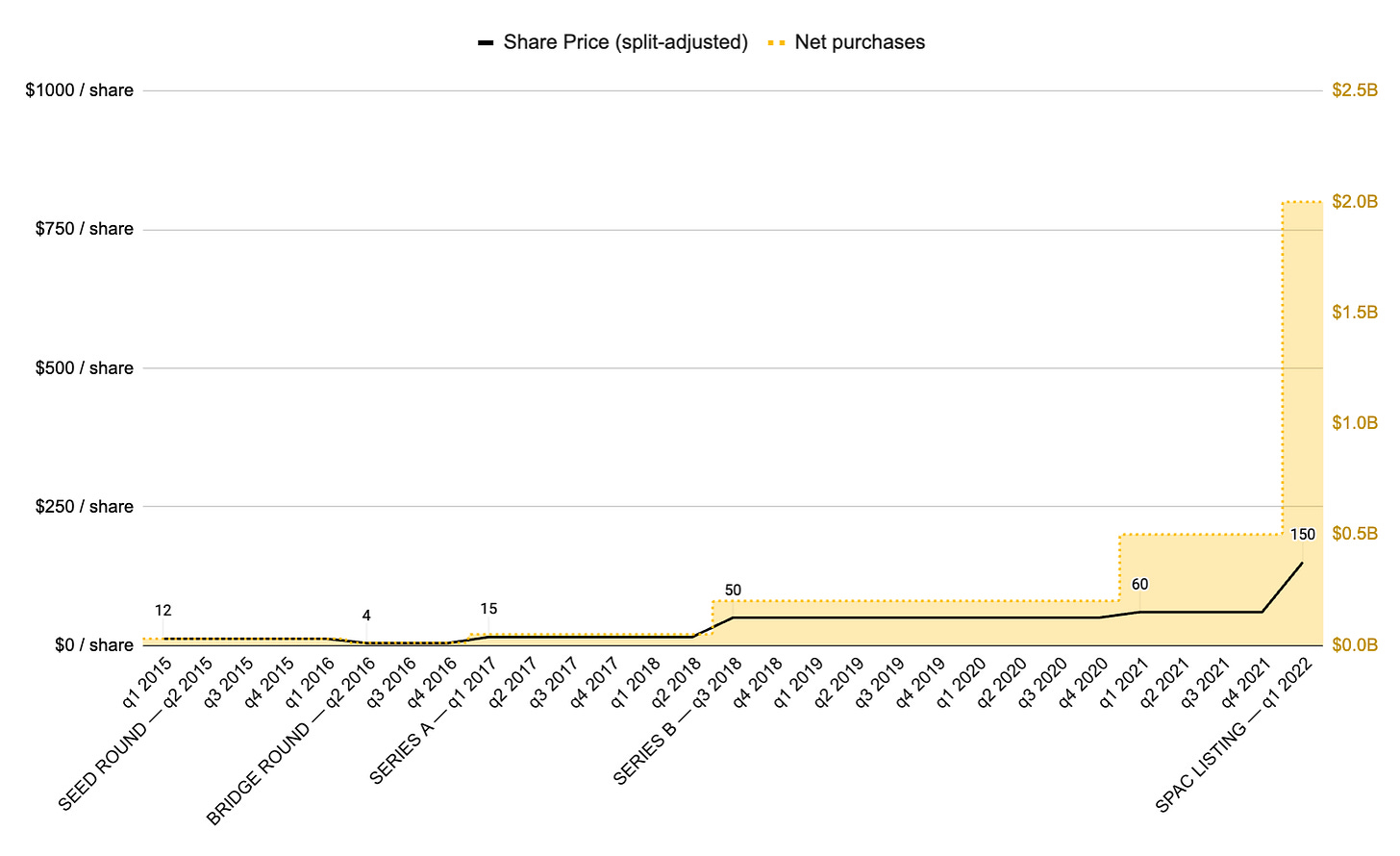

Object lesson: dilution is often an overrated boogeyman, but in some cases it can have a massive impact. Acquisitions, founders cashing out a lot of secondaries, large executive grants, and a healthy IPO offering… those things can kill the multiple. What was, on paper, a 80x in the valuation turned into a 12x in the share price.

Compare the black line and the yellow area below — they start in lockstep; the divergence over time is the impact of dilution:

But wait! For a brief while, it spiked to nearly a $10B market cap in the public markets. Woo!! This is how it's supposed to go. Maybe it's not going to last at $10B (60x), but at least it's healthily above the IPO price! Maybe it'll settle at $4-5B (25-30x).

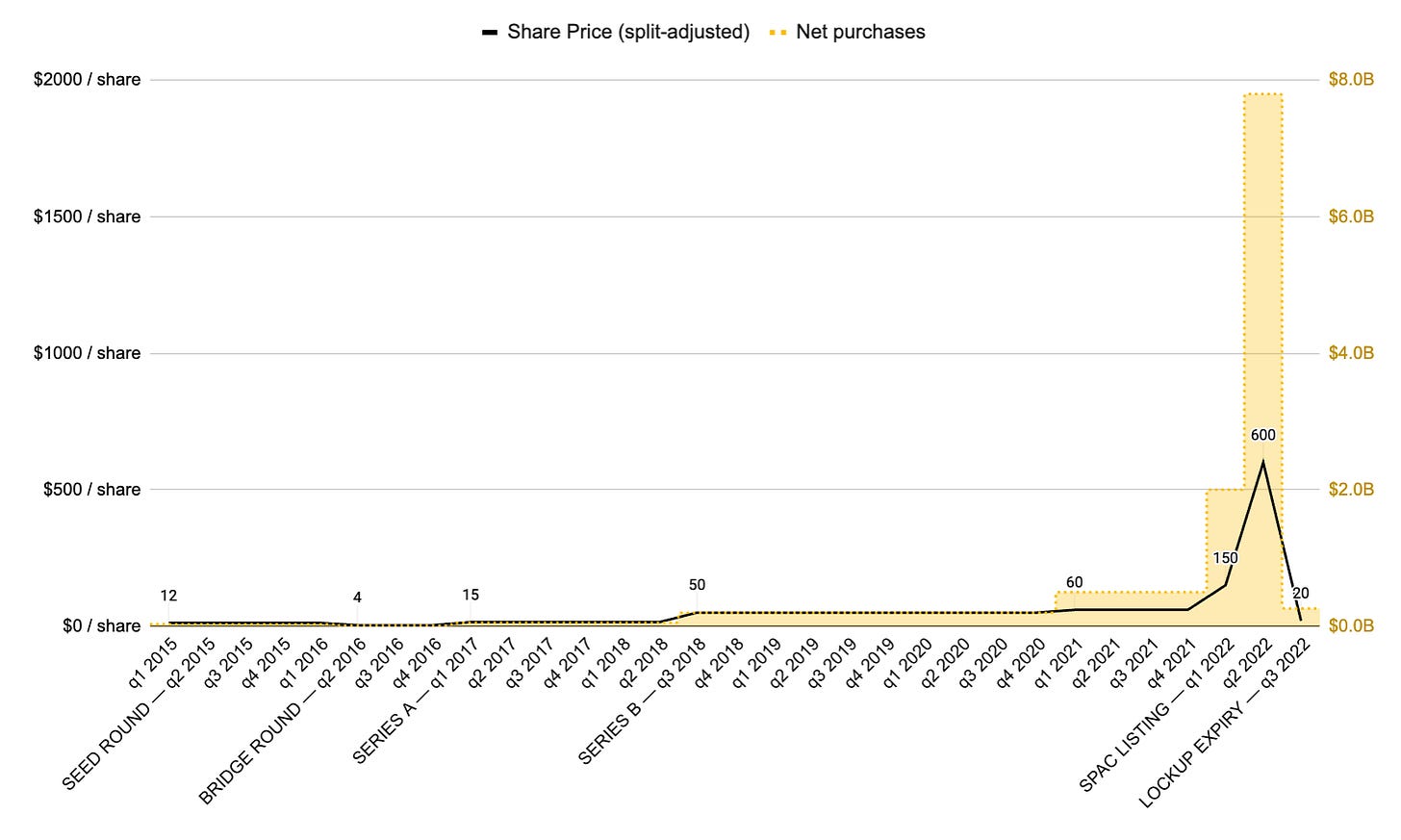

Not so fast. This was in 2022. By the time the lockup expired, the stock was down 97% from the peak (and down 87% from the listing price), trading at $20 / share:

That's right: in a highly improbable scenario where I joined a seed stage company, slogged for years to get it to $30M in revenue, and then a bunch of other people work hard for several more years to scale it past $100M in revenue...

The share price grew ~67%. It turned out that I’d have been better off taking that money and putting it in the S&P 500 (SPY grew 90% from $200 to $380 in those 7 ½ years).

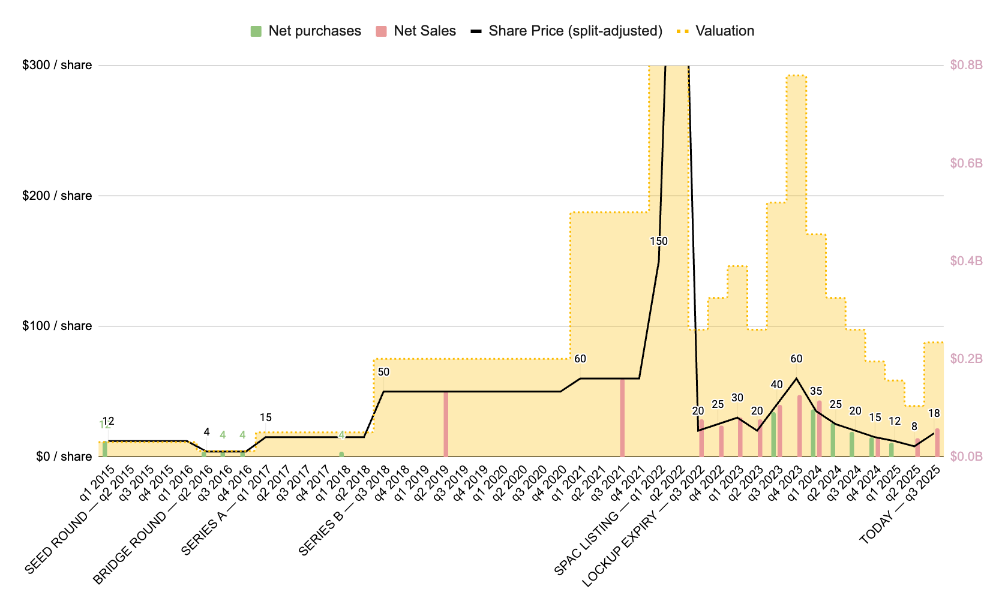

Here’s the whole story, including all my purchases and sales, grouped by quarter (bar height = purchase price, not quantity):

Does that mean you shouldn’t join an early stage startup?

Not at all. I’ve also seen it play out amazingly well, too. I’ve worked closely with loads of early employees in the secondary markets. There are a lot of people who made $10-200M from joining an amazing company very early, growing it and growing with it. A lucky few have even done it a few times in a row!

Not so much in this case, ha. But honestly, it ended up being fine — better than most:

My weighted average total comp went from ~$175K → $225K → $250K over my tenure, roughly corresponding to VP Ops at seed → Head of Biz Ops at Series A → COO at Series B.

All along, I was drawing a $100K salary, so it was only the equity that increased along the way.

Across my original grant and the modest refreshers (kicking myself for not fighting for a COO promo grant), I got ~55k shares. In total, these grants represented $500-600K in equity comp over 4 years at the company’s preferred price when they were issued.

This felt low to me, so I made up for it with my secondary purchase + voluntary paycut, which added another ~25k shares (at a cost of ~$100K out of pocket).

In total, I had vested and purchased ~80k shares. I sold ~20k shares along the way in 2019 and 2021. Since then, I’ve bought & sold more at varying prices post-IPO. I currently still hold ~20k shares.

My weighted average exit price (marking shares I still hold at today’s market value) was ~$32 / share.

Fortunately, those seemingly reckless moves to double down on the company actually ended up being a decent decision because they were done on a very low basis ($4 → $32).

But overall, it was a very bad risk-reward equation. I gave up ~$700K in opportunity cost + out of pocket cash for a 3-4x payoff, which — when you consider the extreme improbability of a company going from early stage to IPO (5%? odds) — makes zero financial sense.

A notable benefit was the better tax treatment in this path. The majority the equity was tax-free thanks to QSBS (it can be a hugely impactful tax break for those taking startup risk). The 3-4x improves to 5-6x when that is factored in. Still makes no sense though (6x * 5% is still a 0.3x EV!).

But I still strongly believe that asymmetric bets are still the name of the game. I’ve made lots of decisions that carried limited upside and uncapped upside, and I’m really glad that I have. For example, the same risk-prone mentality has paid for itself many times over with angel bets.

(Fortunately, my wife has highly marketable skills, so we’re able to sustain a stable lifestyle off her career; marrying up is a secret weapon when you’re building startups.)

Some things aren’t just about money

I’ve now been a founder for the last 7 years since I left that company, which has amplified a lot of those tradeoffs (albeit with control over my company, and hence my destiny). The majority of that time has been no-salary. Across my 11 years in startups, my *total W-2* has been ~$600K (<$60K / year). I’m not in this to get rich quick, I'll tell you that much 😂.

Startups are like playing blackjack... so "winning" might mean a big payday, or simply having the dealer bust a face card against your 17 (i.e., a scenario where the win is expected but modest).

But if you’re playing blackjack right, you’re not doing it for the money, you’re doing it for the entertainment, for love of the game, and to have a good time with friends. The journey is the destination.

But that journey… I’ve learned so much. Grown so much. Gained so much.

I’ve felt the magic of true PMF: your customers want to rip the thing out of your hand faster than you can make it. It stressed me the fuck out. But when I don’t have it, it’s all I crave.

I’ve gained some street cred. Secondaries were a nascent, taboo industry when I was building in the space, and it’s since become sexy. I’ve lucked into some great angel investments. Sometimes, I get messages from strangers telling me that they love the work I’ve poured myself into (Forge, AbstractOps, Fair Offer, Autograph, the Weighing Machine, or my writing). It genuinely gives me warm fuzzies (my love language is words of affirmation).

I’ve gained an incredible network, joined amazing communities, worked with awesome people, formed lifelong friendships, and gotten some incredible investing dealflow.

My biggest regrets: I wish I’d learned to sell better. I wish I’d learned how to code earlier. I wish I’d focused more. I wish I’d held a higher bar for talent and culture, rather than making compromises because I felt like I had to grow headcount faster. I wish I’d raised less money at lower valuations. I wish I’d understood that 10x people are very real: they can actually flip a binary no to a yes, or produce such insane leverage that you wouldn’t think it was possible.

I’m glad I’ve taken on the occasional risk of being screwed over in order to be vulnerable and open with people and I don’t regret a thing. Because when I did get screwed over, it taught me the kind of person and the kind of founder I wanted to be. How to build the sorts of culture I wished every company had. How to be better in each year than the last.

And finally, I’ve come to understand what I care about, in order:

Winning (= building something big)

Working with brilliant people who are good humans

Doing right by stakeholders (employees, customers, investors)

Having fun along the way

This is the only way I can imagine it. This is my life. There are many like it, but this one is mine.

Hey Hari, thanks for sharing this extremely transparent and realistic history. Sounds like a very tough grind! There is a tendency to romanticize that startups will make you financially independent, but the reality is years of work for a low probability return -- The journey is the destination, and the learning and network are the rewards!

Thanks for sharing, Hari!

I worked at two improbable startups: one that went from seed to $1B series C and another late stage startup that raised $500M round at $4B with an imminent IPO. Yet to get a liquid $ from either equity :)

It’s a better financial bet to join public cos that can grow from, say, $5-10B to $100B, or even $100B to $500B. Startups don’t offer enough equity to non-founders to cover for the opportunity cost.