Building a Company is like Playing Blackjack

We had an odd first few years at Forge.

I joined a ~year in, as a founding team member at the start of 2015. The secondary market didn’t exist 10 years ago — secondaries were basically a dirty word then.

Knowing what I know now, Forge (which was known as Equidate at the time) was one of those rare companies that was born with product-market fit: we could go say to early employees “we can get you some long overdue liquidity,” and we could go to angels and family offices who (at the time) had very little access to private markets and say “we can get you exposure to some iconic companies” (Airbnb, Uber, Dropbox, Snapchat, SpaceX). The 2-sided demand was not the issue. It was just a complex legal, compliance, and operational execution game.

They were three scrappy guys in a living room in SoMa when I joined. The company had just closed its first backlog of trades, and we were starting with a fresh slate on some new deals. We tripled revenue QoQ in the first few months of that year, and it was very exciting.

About 4 months in, we got subpoenaed by the SEC. Fun story (/s) for a different time, but the TL;DR is that — while we worked through that issue — we couldn’t really transact via our proprietary trading instrument. So our revenue went nearly to zero for the rest of 2015. Gil Silberman, one of the cofounders (who recently passed away, rest in peace), said “we’ll sell broomsticks if we have to.” I remember thinking “I’m going to do whatever it takes, put this company on my back if I have to.”

At the start of 2016, we hired Rob, a new head of BD. A few months later, as legal bills from the SEC issue piled up, we nearly ran out of money. I think we had maybe a month of runway. The team (except Rob, since it was a bad look to ask a new hire to take a hit) took 50% pay cut. It looked dark.

Then in Q2, we closed an emergency (down) round and settled the SEC issue, back to back. After that, our growth was incredible. Our annualized net revenue graph looked something like:

We went from basically ~$0 revenue to ~$30M in about 2 years from early 2016 to early 2018. Back in the pre-AI era, that wasn’t really a thing.

We went from struggling to recruit good people, to a spot where incredibly talented people were eager to join us.

What’s wild is that — aside from an increased emphasis on institutional relationships — we weren’t doing anything that different between the start of 2016 and the start of 2018, but our revenue exploded >100x in that time and was actually accelerating as we built a brand and network effects. So what made things suddenly work?

It was a crash course in understanding just how big a role luck plays in winning — including, of course, luck of your own making.

Which brings me to…

Blackjack

Startups are very affected by luck, but they aren’t a lottery. It’s not like every action you take is random or a long shot. But you do actually take a lot of shots.

When we were making bets at Forge, it felt like a series of 50/50 decisions, coinflips. Do we work on this deal or that one? Do we build this feature or that one? Hire this candidate or that one?

Every time, you decide how much you want to invest in a given decision. Depending on how they go, you win, lose, or tie.

It turns out this is a lot like Blackjack.

Every player has a chip stack. The startup is the runt at the Blackjack table. The one with $100 when the table minimum per hand is $10. The incumbent 800 lb gorilla is the player with the $10,000 chip stack.

Competition

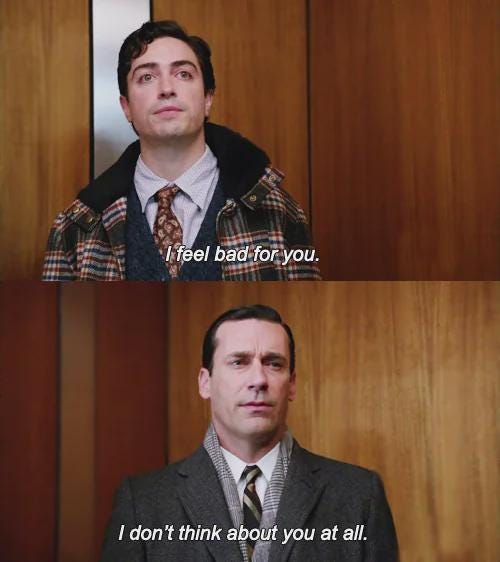

You're the startup, and you love the thrill of the game. Every hand matters. You're having fun. You look over at the $10K chip stack and see BigShot is betting the same $10 you are. What a joke. BigShot glances over and smiles to be friendly. Here's what you and they are both thinking:

The players aren’t playing each other. This isn’t poker. They’re both playing the dealer.

The startup is not really competing with the incumbent. If they are, they're playing the wrong game. And the incumbent doesn’t really care about the startup. Not yet, anyway. They’re both playing against the market.

Placing bets

As a startup, you obviously don’t get infinite coinflips. In fact, you actually get deceptively few. It turns out that most decisions sort of don’t matter. You work on a deal that closes, and another couple that don’t. You win one hand, lose one hand. That is execution -- it's essential work. You have to play every hand. But it's not a decision.

In fact, the only decisions that matter are a few big ones: you split the 8s, get a 3 and a 2. You have 11 and 10 against the dealer’s 5. You double down on each. You win big or you lose big.

BigShot on the other hand… the big hands aren’t actually that big for their chip stack. So after a wild swing they might go from $10,000 to $9,700 to $10,200. Whoop-de-fucking-doo.

A few rounds on the Blackjack table later…

The only way to win in Blackjack is to make lots of money against the dealer. And that can’t happen in one hand. It would be a terrible idea to bet your entire stack on a single turn, no matter the hand you were dealt.

Instead, you try to build on a series of modest wins. After the first 100 hands, if you’ve played the odds correctly and had some luck… let’s say you had 5 hands where you doubled down or split, and you won all of them. Now you’re at $250 instead of $100.

But you’re a risk-taker. So now you don’t bet $10 a hand, you bet $25 a hand.

In the meantime, someone comes up to you and says “Can I stake you another $150? You keep some 50% of my gains and give me back 25% of the losses.” (That’s a VC, obviously. And I know this is not really legal in a casino, this metaphor isn’t perfect okay?)

You have the same sort of run again. Now you’re at $1,000. Even net of what you owe your backer, you now have $925.

You raise the stakes a bit again. Not quite proportionally — you have to preserve some of your gains of course. Let’s do $50 a hand. BigShot is looking at you like you’re crazy. You’re loud, everyone’s rooting for you. BigShot starts to bet bigger, too — now they’re doing $100 a hand.

The dealer gets a few Blackjacks in a row. Now you’re back down to $750, and BigShot is down to $8,500. Ouch. (That’s a market downturn.)

Bitter, the whole table pulls back. You bet $30 a hand for a while. You get on your third streak, and you’re suddenly up to $2,000.

Rinse and repeat.

There are very few decisions every year that are company defining. Early on, there might only be 5 of these a year. The honest truth is that you often don’t know for quite a while if this was one of the defining decisions of the year. You just do the best you can, with the information you have at the time.

If the average new buy-in player has $100, maybe some people start with $50. Maybe that startup is from the midwest and this is their first time playing, or they don’t have jazzy credentials. Some others start with $300. That’s like someone with just the right credentials at the right time — they’re starting from second base. No one said life was fair. But every hand has the same chance against the House.

And just like with Blackjack, you can give yourself an edge. You can learn how to count cards. That’s like being a serial founder or operator with prior exits. They’ve played a lot before and they know when to double down when the count is high, or lower their bets when the count is low.

If you’re tipping the dealer, you’re dedicating resources to something that doesn’t matter for winning. The House doesn’t care if you tip the dealer. The Market doesn’t care if you’re donating some of your profits to the Red Cross. That’s not to say you shouldn’t do it — being a good corporate citizen is nice. But it also doesn’t change whether you win. And you certainly shouldn’t do it until you have a bigger chip stack. Survival is more important than generosity.

Blackjack tables sometimes have “side bets.” These are long-odds that you can place that pay off big (e.g., 50:1 or 200:1) if they win. They’re fairly bad expected value but feel good when you win. These are the “skunkworks” or side projects that a company might undertake. Putting $5 on these when you have $100 is stupid. But maybe putting $20 on these is one of the only low-risk ways to move the needle when you have $10,000.

Blackjack also has a few varieties: single deck, double deck, switch, Spanish 21. Many tables pay 6:5 on Blackjack and others pay 3:2. They all have very different odds and very different strategies. A strategy works in one usually falls flat on its face in a different game. As you probably guessed, this is the “market” you’re playing in: consumer vs. healthcare, B2B vs. hardware. Ideally, you want to avoid the markets with terrible odds and try to pick the good ones… unless, of course, you really enjoy Super Fun 21, in which case — go for it, I guess.

It usually doesn’t matter whether a table “looks hot.” You might have a table with lots of people cheering, and people hovering around to stake apparently-hot players. But this isn’t really an indicative signal of future results. By the time you get there, the high or low count has probably been arb-ed away. And it could have just been a brief spurt of luck... which led to every player over-extending their bets and busting in the end.

You also have to make sure you're properly incentive aligned with the backers. There's a fine balance in terms of how much leverage their capital can add for you, versus feeling like keeping them happy is more important than the right answer. And you should probably avoid loan sharks (aka venture debt).

It’s important to remember the dealer always has the edge. If you start with $100 and play perfectly, you lose all your money in ~100 hands. You have to stay ahead of the game just to survive. Maybe 10% of players leave a casino having made any money.

But the most important takeaway here this is a long game, and wins and losses compound. If you’re making smart bets every time, ideally while counting cards, and you’re patient and don’t make any reckless decisions (and you’re not putting away too many free drinks), your $100 becomes $500 and just might become $3,000 in a few hours.

Have fun. Just remember your limits, and try to quit while you’re ahead.