What I wish I'd done differently with AbstractOps

All successful startups are alike; each failed startup is a failure in its own way

– Tolstoy if he lived in 2023, probably

AbstractOps is the company I founded in 2019, and this is a retelling of the ups and downs over the next 5 years.

This was one of the more frustrating and painful posts I’ve written lately, so I apologize that it doesn’t have the quirkiness or joy that I usually aim for. I needed to share it anyway. I hope it helps others, but more importantly I want the story to be told.

This is not a post-mortem; AbstractOps is still alive and doing well, and will even be profitable shortly. Rather, it’s a retrospective — of what was, and what could have been.

The things that didn’t work are roughly grouped into: product decisions, go-to-market decisions, and company decisions. But first…

The rise

AbstractOps was an incredibly cool premise, and one that we had a real shot at — if many more things had gone our way.

We were building the OS for the back-office. Every founder desperately wants this. It’s just a really great problem. If we’d solved it, it could have changed how early stage companies are started and built. The promise still gives me goosebumps, sometimes.

The early days — especially fundraising — were hard, because I was a solo, non-technical founder, building hybrid product + services (when this was still uncool). Plus the company I’d previously helped build (Forge) wasn’t well-known yet, and I was founding team (not founder) there so I didn’t have the same street cred.

But after some early customer traction, a clearer pitch, and some no-code prototyping, I managed to raise ~$600K at $5.5M postmoney. I brought on a couple of cofounders, Adam (still one of my closest friends and a wonderful person), BK (ex-Superhuman, to lead engineering). COVID hit and we went fully-remote; we added several talented founding team members over the course of the year — Charles, Loubna, Anthony. Based on a combination of promising product prototypes and Adam’s great sales skills, we grew to nearly $100K in ARR in a couple of months, catalyzing a seed round (~$3M at $16M postmoney) led by David Sacks and Lainy Painter at Craft.

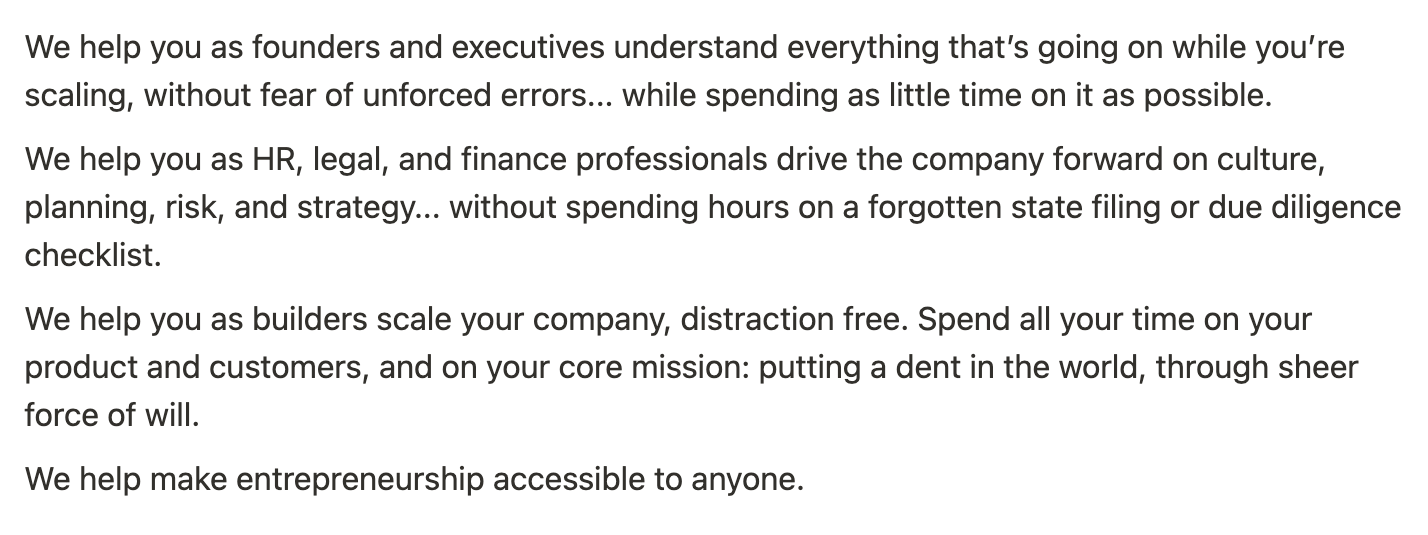

By this point the software vision had come nicely into focus — the business & operating graph of your company, powered by an (actually very powerful) internal no-code engine. This enabled a wide variety of workflows:

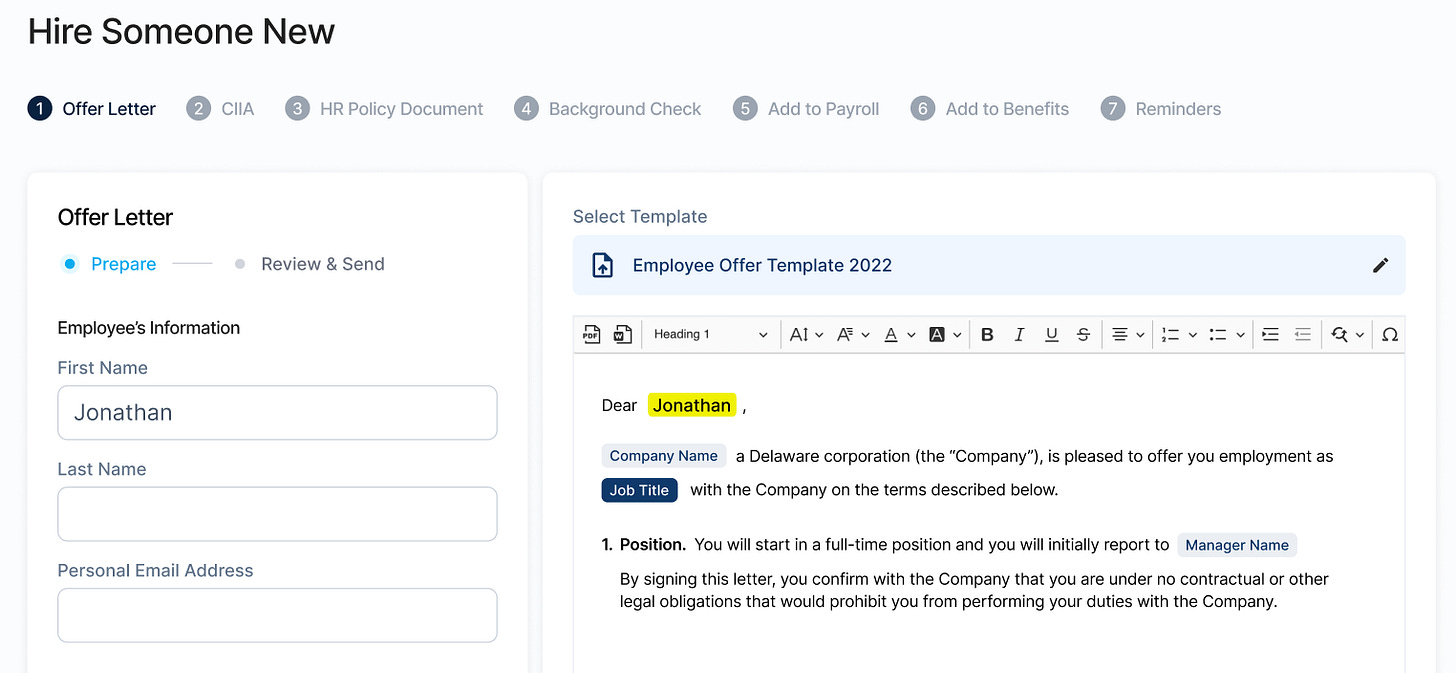

By popular demand, the AbstractOps offering was a hybrid product / services offering. The product had broad (as we found out later, too broad) capability, but the hands-on operator would fill in the gaps, and be a founder’s consiglieri (with the goal of becoming an "account manager" or CX over time, as the product automated more of the manual work).

This meant we could charge services revenue, not just SaaS. Our monthly fee per customer went from $200 to $400 to $800 to $1,500 to $2,000+… with no real impact on demand. And customers really liked working with us. We helped companies scale, fundraise, hire, fire, pay, comply, and everything in between. A client once — unprompted — recorded a video of their whole team thanking and cheering their point of contact (and AbstractOps) for playing a critical role in enabling their fundraise. I cried with joy when I saw that video.

We even raised a small angel fund for Adam and I to invest in AbstractOps clients — because why not?! (or so it seemed at the time. Our customers loved us so much we got into several oversubscribed rounds because we were a strategic ally.

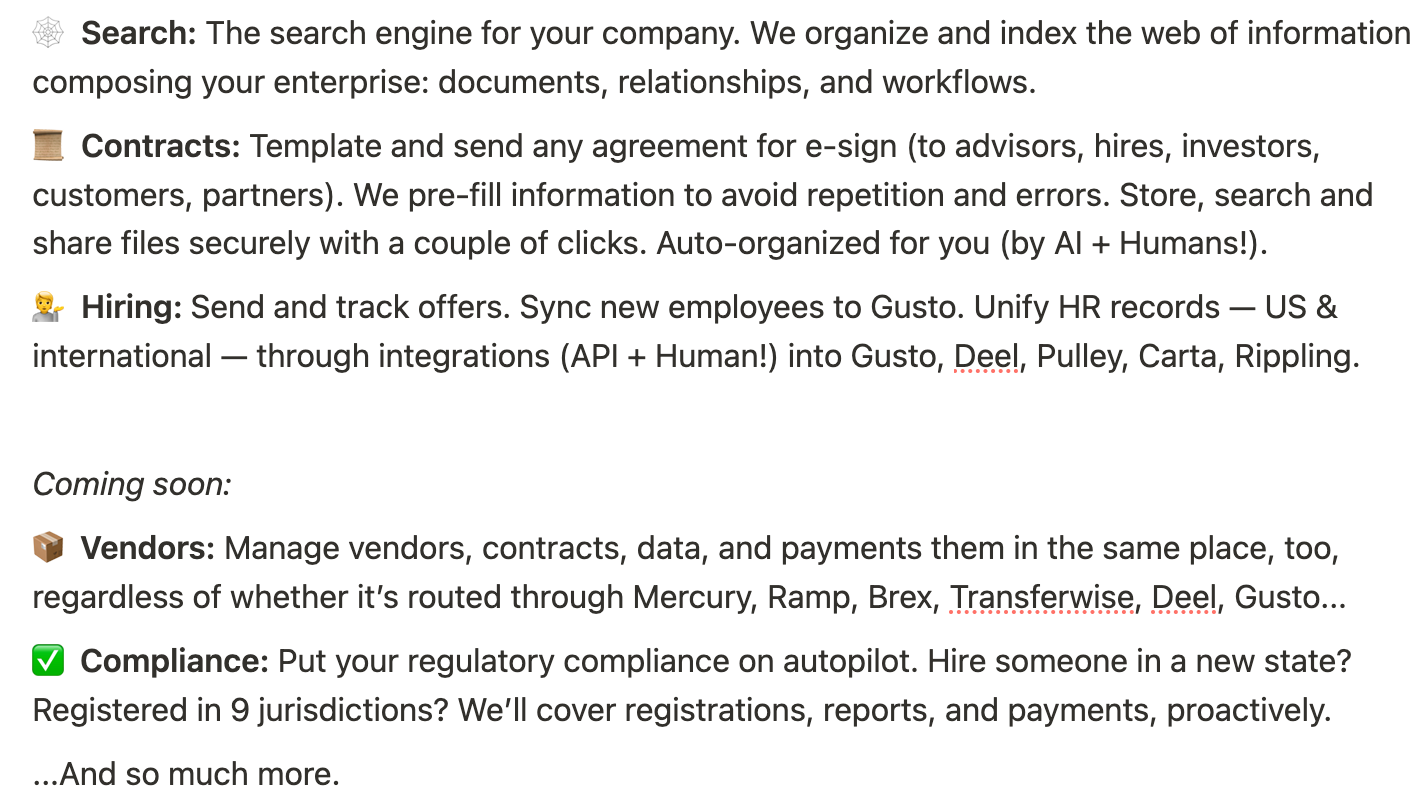

So we rapidly scaled 5x to $500K in ARR by mid-2021 and brought on some awesome execs (Pooja; and later Amar, Ray, and Rebecca). This led to us raising a “Pre-A” as we called it in that brief, crazy time: ~$4M at $60M postmoney. Overall, we had an insane cap table — while fundraising isn’t indicative of success, I’m pretty darn proud of our all-star lineup:

The fall

That fundraising announcement was in early 2022. We kept growing — peaking at ~$1.5M in ARR in March 2022, and we raised $1M at $100M postmoney. Gosh, this was absolutely absurd in retrospect; I felt embarrassed enough about this in the months that followed, that I went back to the investors to proactively recap it back down to the previous $60M valuation. My friend John (and angel investor in AbstractOps) recently called this sort of thing a suicide round. There were all together too many of these rounds in the crazy days between early 2021 and mid 2022.

When the market correction happened in Q2 2022, it exposed the cracks in the foundation — in AbstractOps and every other company. In our case, these were:

our ARR had ~35% in contribution margins, but closer to 20% in gross margin, which simply cannot work for a scalable business

this meant that while our revenue multiple was high, our gross profit multiple was wild (I’ve since come to realize this is the most correct way to value a company); if ~70x revenue seems bad, 300x+ gross profit is worse. This was comparable to a software business that had raised at a 250x revenue multiple.

our culture was a constant challenge. We made the mistake of setting the expectation of rapid promotion and a consensus-based decision structure which resulted in frustration and gridlock far more than was necessary. It was easier to resolve these when everything was working, but when the rocketship sputtered, both the expectation of upward mobility and the desire for consensus made things a lot harder.

attrition was a huge issue, and the attention to hire / train / manage / fire people occupied more than 50% of the founders' day-to-day bandwidth

my cofounder and I each had valid but divergent visions; I was more product-motivated (even if it delayed growth), and he was more revenue-motivated (even if it was achieved through services)

the product had simply not delivered on the promise yet, in part because it tried to do too many things

the things the product did well, people didn’t want to pay for (e.g., contract lifecycle management, recordkeeping); and the things people wanted to pay for, we did a mediocre job of (e.g., hiring workflows, payments, state compliance)

fundraising was no longer a viable strategy to “make it work”

In hindsight all of these things are crystal clear, but in the day-to-day none of them are obvious. Each individual decision made sense at the time, but in totality painted us into a cornered situation where the company simply couldn’t work.

Around late June, it was clear to me that we had to make a set of drastic changes. In the 12 months after July 2022, the company saw 2 cofounder breakups, 3 rounds of layoffs (from 38 to ~5), a hard pivot and a couple of soft ones, a company spin out, a ~90% drop in revenue... and finally a soft recovery.

At this point in the fall of 2023, it was abundantly clear that this would be a healthy “lifestyle” business but not a venture scalable one, requiring a CEO and leadership whose strength was in tactical ops and demand generation; not 0-to-1 product, which is my passion. So, I decided to step down as CEO, hand over the reins to Kristin (AbstractOps’ current CEO, who had risen rapidly through the ranks), moved into a supportive chairman role, and terminated my vesting.

Today, AbstractOps provides state compliance automation for companies operating in multiple states. It’s a healthy, growing business with 200+ customers, strong NPS (80+!), and nearly breakeven. It will continue on as a cashflowing, dividend business (or eventually, a strategic acquisition for a payroll company).

This is by no means a “failure” but… I certainly failed to lead the company to the promised outcome (a venture-scale business with a big exit). There were thousands of small decisions that led to this, but a couple of dozen critical things that didn’t break our way, about which I still wonder “what if”.

Product decisions

Tech-enabled services are very very hard to build in a venture-scalable model. I wrote a whole other post just on this topic. It’s one that’s resonated with a lot of people but the main factors are: the people overhead really impedes the company’s ability to scale effectively; revenue is higher than software but customer expectations are sky-high too (and hard to execute on reliably); cultural factors dominate (and culture is hard and slow to build well); and gross margins are very hard to get up to venture-expectations (60%+ at an absolute minimum, ideally closer to 70-80%).

I was a novice product leader. While I’d worked at a fintech startup before, it was much “fin” than “tech,” and the lack of product intuition at the time resulted in a bunch of rookie mistakes. The CEO has to be the product visionary, but my instincts hadn’t yet caught up with the needs of a true software product CEO.

We tried to do too many things. I remember one internal memo had the following line: “we’re building lightweight Rippling + lightweight Bill.com + lightweight Ironclad.” At the time, it seemed simply ambitious (it was 2021, everyone thought they were going to take over the world!), but given the nature of product development at the time, it was simply absurd.

I didn’t understand that the [cost to build] vs. [the cost to build something delightful and maintain it] was roughly 1:5. I really didn’t internalize that >>50% of the engineering cost (in resourcing, specifically) — maybe even 80% — is after the v1 is shipped.

We were too early, and to paraphrase Howard Marks, too early is the same as being wrong. Our clever document vault concept? We spent months of engineering time building document AI in 2020-21, to get the classification to >80% accuracy on >80% of documents. We were so proud! Today, that’s a day’s work with an OpenAI API call. And the sort of surface area we were signing up for was impossible with the engineering capacity we had at the time; today, I think it’s possible with just a few 10x engineers leveraging Claude Code.

Subject matter expertise is double-edged — too often, we built based on knowledge not users; so we built things that were often technically correct, but didn’t map to our users’ understanding or mental models. Unless you’re building a tool for power users (we were doing the opposite), the product has to guide you through what needs to be done. E.g., we had 50+ types of documents a user could send for signature. We should have picked the top 5 and left it at that.

Even so — the contract product we built was incredibly delightful. I still miss it, and many customers still tell me they do, too. You could edit the inputs and see the draft document update live, but retain all the field values for reference later (so you know what you sent without having to reopen the PDF). You could edit the actual legal terms without mucking up the formatting of the field values. I’ve still never seen anything quite like it. I hope someone else builds a truly delightful contract lifecycle system.

GTM decisions

Defining a new category is insanely hard, even if it sounds exciting. You never, ever want to have to educate users on the value of your product. The pain points were obvious to us, but we couldn’t describe it in 5 words or less, and the need for good process / automation is not easy or pressing for our customers — which were founders (who, correctly, only cared about PMF). The only aspect they did know and care about was operations capacity / know-how to simply “deal with it”; but capacity and knowledge require a person, not software, to solve (until AI, anyway).

General purpose tools (Airtable, Zapier, etc.) are hard to do well. Every single such platform that succeeded, did so with specific (1-3) use cases. We didn’t know what this was, with clarity; by the time we arrived at the right ones (state compliance, payments), it was too late — the ACVs weren’t big enough, and we didn’t have enough time or money to reorient the product around a supersized version.

We picked the wrong ICP — we should have built for mid-market / enterprise, not early stage startups. The main reason is very simple: ACV, and as a result sales efficiency. Thiel’s SaaS “dead zone” is spot on; it’s hard to scale products with an annual contract value between $500 - 5,000. Early-stage companies of <10 simply do not pay >$5,000 / year for software. The only exceptions:

computing (cloud, and now AI)

professional services

This makes it quite obvious why we were pulled into services.

The only alternative is if you onboard an early stage company to the product early, because it clearly scales to mid-market. But since we had such a wide surface area, our product lines weren’t robust enough that we could scale with a company to 50-100+ people.

Legal products are hard to sell. Non-lawyers don't really want to think about or touch it. Lawyers are very risk-averse to adopting your products.

That said… we did build something (an offering that was mostly services) that generated a significant amount of customer love. We helped hundreds of customers build and scale easier. At the peak, we crossed $1M in ARR — a milestone that the vast majority of startups never reach. For that, I’m grateful.

Company decisions

As a company were obsessed with process — possibly because of the operational DNA. One of our execs joked that we had more SOPs than the number of times we'd run the SOPs. In retrospect, we shouldn't even have written something down until we had already done it at least 10 times.

We talked way too much about culture. We spent more time talking about values than reinforcing them through behavior. Our focus should have been on scalable product-market fit because without that, the company would die.

A company that dwells on work-life balance is not going to make it. This was an unfortunate and common theme in 2020-21, due to the chaos and stress of the pandemic, followed by the talent wars. To be clear: burnout is real, and people do need downtime in order to recover and recharge. But making a big deal about work-life balance was a disaster. My cofounder and I worked many weekends, but we literally hid it from the team with scheduled Slack messages, to “set a good example” on work-life balance. In retrospect, what the fuck. We should have sought people who wanted to work crazy hard on important problems, and who were thirsty, even desperate to get to product-market fit.

Constraints breed creativity. We should have raised a lot less money at much more conservative valuations. This is probably the only thing I will give myself a bit of a pass-on: everyone lost their minds in 2021, due to low interest rates, historic growth rates, and easy money.

The “cost” of capital is not just dilution, but also increased expectations. Once we’d raised >$5M, there is an implicit expectation to scale revenue. This isn’t something that was imposed by our VCs, to be clear; it’s just a market level expectation to seem like a startup that is “killing it” vs. one that’s treading water. If we hadn’t raised that capital, we could have stayed in “exploration” mode. Which means…

We scaled something that wasn’t ready for scalable product-market fit. The services had PMF but weren't scalable. The product was scalable, but didn't have PMF. We thought we'd figure out the combination and repeatability "later" — this was obviously a mistake. Once you take on customers, you have an obligation to keep serving them and exercise duty of care. We never let anyone down; but if we had had fewer customers, the transitions and pivots would've been a hell of a lot easier.

Price's Law was very real for us (50% of work is done by sqrt(team)). When we went from ~38 to ~12 after 2 layoffs, our aggregate (not per capita) productivity was higher than it was before the cuts. This was due to stripping out consensus-based decisions, and eliminating make-work.

But today, AbstractOps serves hundreds of customers with an extremely efficient and lean team and an incredibly high NPS. Whatever the decisions were, getting to that point is not something I take for granted.

Conclusion

Gosh. Just… so many things that could have been done differently. I suppose all we can do is not to make the same mistakes again. After all, there are so many new mistakes to make and learn from!

When I stepped down from AbstractOps, I started a new company. I’m trying to take every lesson to heart. Here’s my cheat sheet:

Stay away from services (except implementation)

Stick to existing categories or well-understood pain points if at all possible

Pick specific use cases and jobs to be done, not a generic / horizontal platform

Pick a ICP (segment/buyer) that has the ability and willingness to pay >>$10K ACV

Seldom bring up “culture” unless there is a clear deviation from desired behavior

Deprioritize work-life balance; work hard, and recruit people who take pride in doing the same

Raise as little money as possible, at incredibly conservative valuations

Stay scrappy and very lean (one XL pizza team)