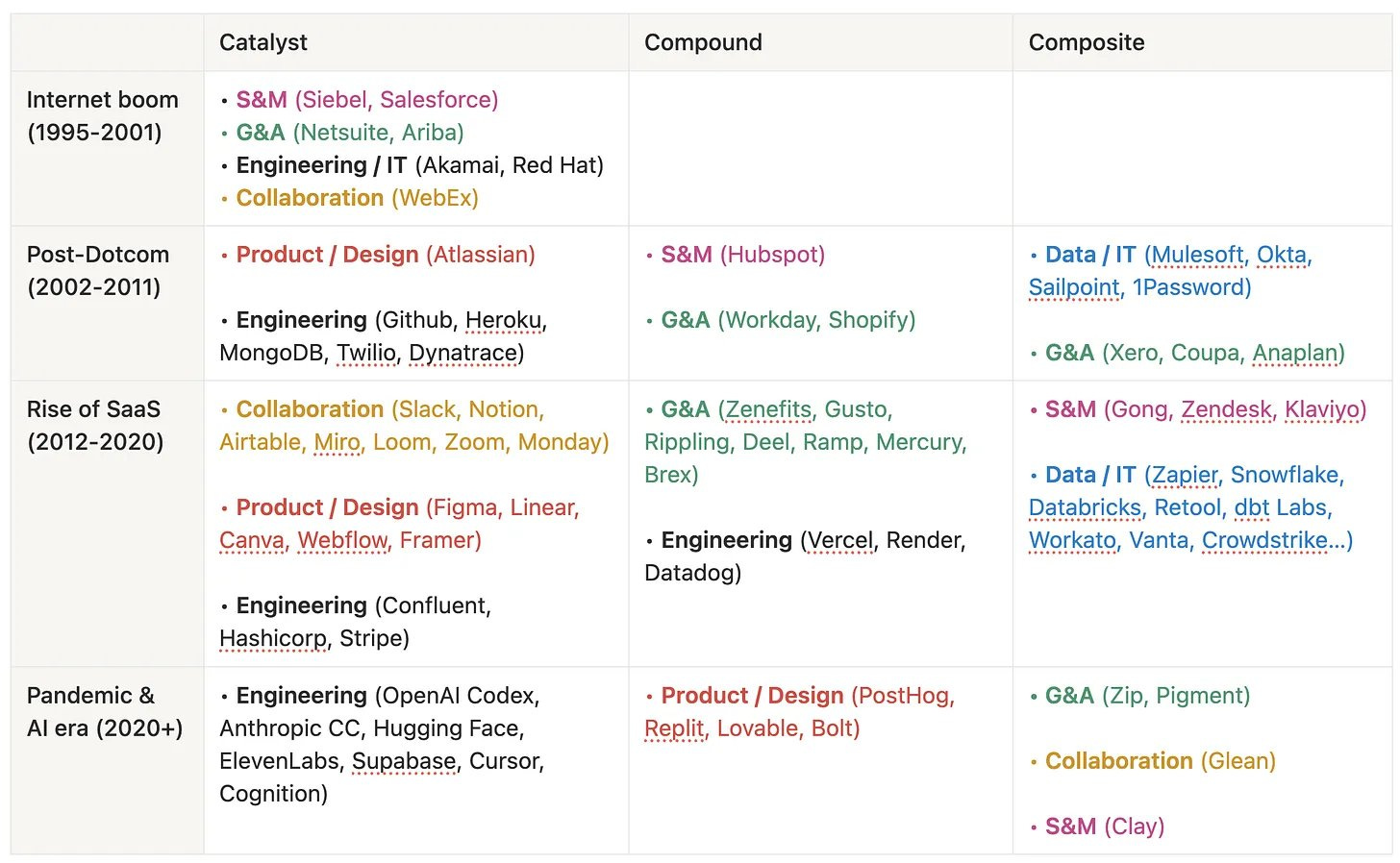

Catalyst, Compound, and Composite Startups

Catalyst Startups

Catalysts inspire a wave of customers or users to change how they operate. Airtable, Notion, and Figma are recent examples of this. There were “relational spreadsheets” like Microsoft Access before Airtable; “company wiki” products before Notion; and product design tools like Sketch before Figma. But these new players were each so gamechanging in their capabilities that users didn’t consider the competition to be viable alternatives.

A Catalyst breaks out of being a Product Company, thanks to an insight or differentiator so profound that it feels totally different than the alternatives. Competition is for suckers.

Second acts

Since Catalysts are supercharged Product companies, their only lock-in is their product quality (prone to attracting copycats), so a second act is essential. Fortunately, they have…

so little competition they have the mental space to build (not just brawl over sales)

so much credibility and mindshare with customers they’ve “earned the right” to do more

Many durable companies have made the leap from Catalyst to Compound over the years (Datadog, Adobe, Workday, Stripe). All of them added product lines: Workday’s HRIS, Financial Management; Adobe’s Illustrator, Photoshop, Lightroom; Datadog’s performance monitoring, log management. Stripe had some false starts (e.g., Stripe Treasury), but other products such as Issuing and Connect have rapidly scaled into large businesses.

Product line acquisitions can also keep pushing this: Workday acquired Adaptive Planning; Adobe acquired Marketo, EchoSign, Behance, Frame; Stripe acquired TaxJar, LemonSqueezy.

Figma and Notion → partway in going Compound (adding several additional product lines).

Airtable → initially bet on a Composite approach (Blocks / Apps) → shifted more compound recently, with Interfaces (Retool-like), Automations (Zapier-like), and Omni (AI builder).

Slack → went Composite over time (Slack Connect, Slack Apps) successfully

OpenAI → going Composite didn’t quite take (custom GPTs, integrations) → went Compound with Codex CLI, Sora, Whisper → trying Composite again with AgentKit and Apps in ChatGPT.

Failure modes

Catalysts rarely fail for going too narrow. The most likely reasons they fail are the product a) had too steep a learning curve, or b) wasn’t differentiated or magical enough for users to care.

Miscellaneous observations

While Catalysts used to appear in any category, in the last decade or two, Collaboration and Engineering are categories that most often produce Catalysts; mostly because their early adopters tend to be technical, creative, or other founders.

Between Airtable and OpenAI: do these anecdotes indicate that Catalysts should probably go Compound, not Composite? Even Slack’s acquisition wasn’t enough to stave off an acquisition.

It’s often necessary for Catalysts to create their category. But they often spawn a community of early adopters and evangelists, and benefit from viral, product-led, and community-led growth.

If you have a mind-blowing product that can change how people work, you still have to explain to people why they should change how they work.

Compound Startups

When operating in a mature industry with well-understood needs, a Compound startup can raise a lot more money, lay shared foundations, and simply rebuild table-stakes very quickly. Rippling did this with payroll, benefits, PEO, HRIS, ATS, performance, EOR, SSO, device management.

I don’t think it’s an accident that most of those products are acronyms; that’s how well defined the product categories are.

The primary factor that makes a compound startup most suitable is the maturity of the category: when the 2nd, 3rd… nth products are extremely well-known.

Any of these products stands alone, but they usually share a customer or industry which allows them to be effectively cross-sold, with better lock-in — creating product network effects.

The second factor that helps a compound startup succeed is when the buyer is an SMB or mid-market company (not an enterprise).

SMB/mid-market is much better suited to a Compound product, because enterprises are notoriously prone to fragmenting their software stack. Enterprises are happy to purchase software that solves that one tiny need better than an all-in-one can: “our team uses 16 different tools, I don’t mind buying a 17th if it solves a problem.” When you have hundreds of people on a team, there are plenty of people to operate 10+ tools. Not so at 50- or 200-person company, where an all-in-one, Compound solution is preferable.

Other recent Compound startups

Ramp, Mercury, Brex (cards, banking, expenses, AP, travel, procurement…)

ClickUp (tasks, docs, forms, automations…)

Vercel (compute, rendering, observability…)

PostHog (product analytics, surveys, tutorials, feature flags…)

Every single product in each of those categories is well-trodden ground.

Failure mode: the ambition trap

It’s easy for a Compound startup to fall into the trap of trying too much, too soon.

Zenefits didn’t fail due to “compliance”; It failed because its operations couldn’t keep pace with its ambition. There were too many product lines too soon, and too little coherence. Before too long, the wheels came off. This no doubt played a role in Parker Conrad deciding to approach the multi-product problem in a more methodical, patient way with Rippling.

Miscellaneous observations

Interestingly, a Compound Startup still needs to have a terrific first act, or wedge; even with all the money in the world, it still takes a while to build out more than 2-3 categories. Rippling built several products from day one, but the value proposition was still very targeted for the first 5+ years (“employee onboarding” from 2017 through 2020; “PEO” from 2020 through 2022).

It takes a long time for “we’re the all-in-one” to become the core value proposition.

In order to do this successfully, the company probably needs to raise a lot more money. This is why serial founders are more likely to build a compound or “fat” startup, versus a “lean” startup.

Financial services is intrinsically a Compound industry. A checking account, credit card, or auto loan is extremely well-defined; and they can be cross-sold very effectively. So every bank offers every product, and tries to grow the relationship with customers to consolidate in one place.

The decay from Compounding can happen over time, too. Symantec, Dell, and Apple all struggled due to bloat, lost focus, and disjointed products — leading to PE exits or turnarounds.

The Composite Startup

A Composite startup builds connective tissue to drive visibility and control for a given function.

This is often relevant for well-developed categories in the mid-market and enterprise. These companies already have a bunch of tools; the biggest problem is not doing an isolated task effectively (most of those problems were solved by Catalysts or Compound companies years or decades ago), but rather in stitching together data or workflows across multiple systems.

A Compound startup wins by providing better cross-functional and cross-system:

visibility (intelligence, insight, reporting), and

control (approvals, anomaly detection, risk management, decision-making)

Typical Characteristics

Composite startups are very well suited to integration-focused and data-focused products.

They grow in value as additional partners or applications are plugged in, producing ecosystem network effects.

For the same reason that Compound Startups are less suited to enterprise but can dominate SMB (fragmented, specialized teams and buyers), Composite Startups thrive in enterprise use cases but will find it harder to tackle SMB (where buyers will pull them to divert focus into lots of product lines). Both styles overlap and intersect in mid-market.

Prominent examples

Salesforce is probably the most famous Composite company. Their service-oriented architecture and App Exchange produced an ecosystem that has made them a hard-to-unseat owner of the customer record, for decades.

Categories where we see a lot of companies go Composite are data warehouses, business intelligence, and workflow automation.

Snowflake and Databricks are a data integration play at the core; they unify, transform, and clean to enable multiple use cases. Segment is similar, specific to the customer data pipeline.

Looker and Tableau are similar, as visualization layers.

In workflow automation: Zapier’s very existence was prompted by fragmentation of data across thousands of applications. ServiceNow, Zip, and Clay are similar in their value proposition (albeit vertical-specific: IT, procurement, and GTM respectively).

Failure mode

The failure mode for a Composite Startup is the lack of a good wedge. There are exponential combinations when combining data from multiple sources; they’re brimming with possibility, so it’s easy to drown in all that possibility, too — when there isn’t a clear first use case.

The (hard) way to solve this is by providing the user the tools to build, themselves. This works for technical users; otherwise, users get overwhelmed in the absence of pre-built use cases.

For example, Airtable was a successful Catalyst, but their attempt to build a Composite approach (with extensions) didn’t take off because there were too many things a user could do; their typical user was not technical enough to build their own solutions. On the other hand: Retool tailored to technical buyers (data engineering / internal apps teams). They also had a great set of initial use cases: customer operations and billing. (We still await Retool’s second act.)

Next up

In the final post tomorrow, we’ll look at patterns: which combination of market environment and industry are most suited to each style of building? How does each type of startup typically stage its second and third acts?

Sneak preview below. Thanks for reading!

This article comes at the perfect time, offering a realy insightful framework for distinguishing between mere product iteration and genuine market catalysis. Your insight into how Catalyst companies evolve into Compound entities is truly brilliant; I am curious, what emerging indicators might we look for to identify the next potential Catalysts in their nascent stages?